Kv3.1

Description: potassium voltage gated channel, Shaw-related subfamily, member 1 Gene: Kcnc1 Alias: Kv4, Kv3.1, KShIIIB, NGK2-KV4, Kcnc1

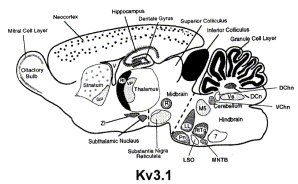

Kv3.1, encoded by the gene KCNC1, is a voltage-gated potassium channel. Kv3.1 plays a key role in regulating neuronal firing, thalamocortical oscillations, sleep, fast-spiking phenotypes in GABAergic interneurons, cell proliferation, hearing function. Mutations to the protein lead to schizophrenia, myoclonus epilepsy, and ataxia.

Experimental data

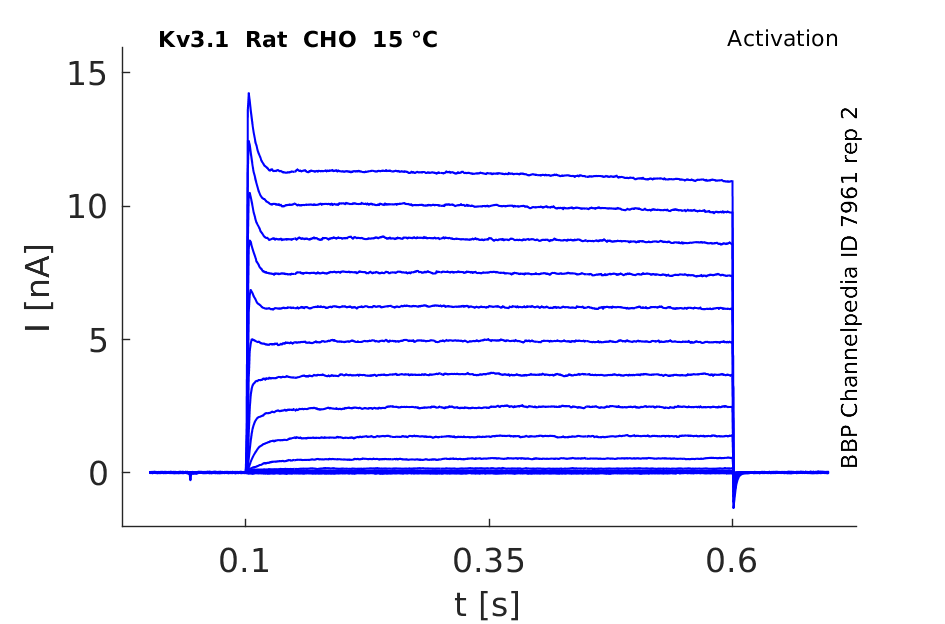

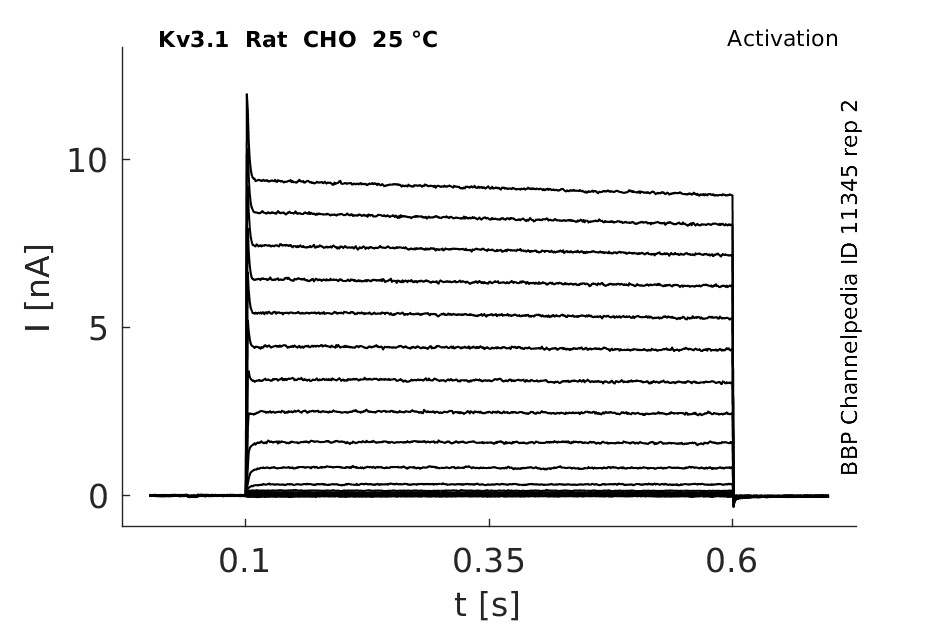

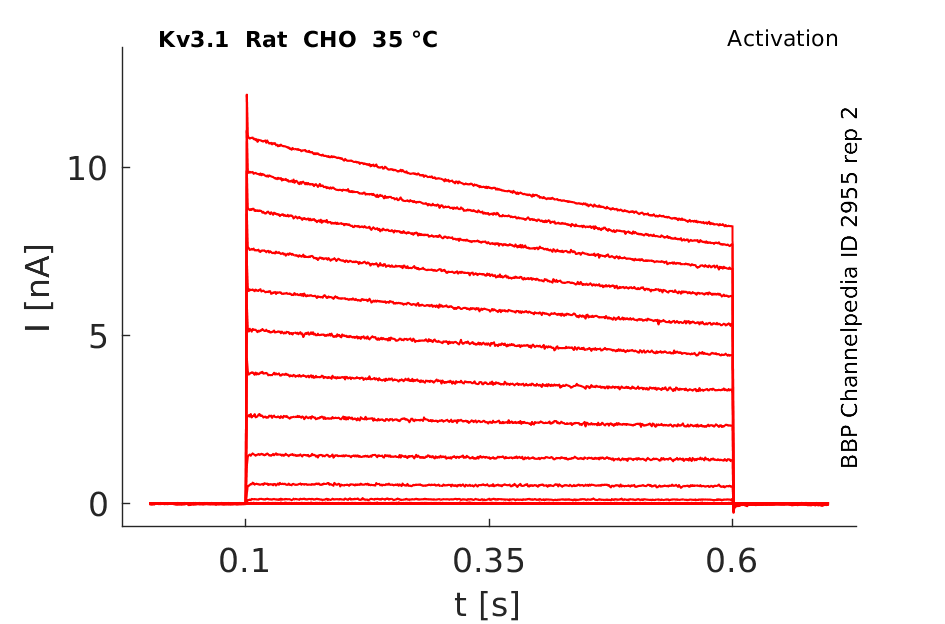

Rat Kv3.1 gene in CHO host cells datasheet |

||

|

Click for details

15 °Cshow 68 cells |

Click for details

25 °Cshow 131 cells |

Click for details

35 °Cshow 90 cells |

Gene

Transcript

| Species | NCBI accession | Length (nt) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | NM_001112741.2 | 4303 | |

| Mouse | NM_001112739.2 | 4336 | |

| Rat | NM_012856.2 | 3975 |

Isoforms

Phosphorylation

Of the 21 consensus phosphorylation sites for CK2 and PKC in Kv3.1, 9 are serine, and 12 are threonine. We determined the incorporation of phosphate into specific amino acids by immuno- precipitating Kv3.1 from PMA-stimulated CHO cells radiola- beled with [32P]orthophosphate. Immunoprecipitates were then subjected to phosphoamino acid analysis [16]

N-glycosylation

N-glycosylation of Kv3.1b informs the association, clustering, and distribution of Kv3.1b in the cell membrane[2094] and to cell compartments.[2095]

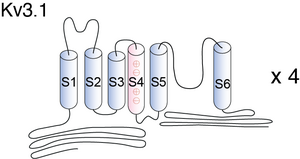

Visual Representation of Kv3.1 Structure

Methodology for visual representation of structure available here

Crystal Structure Kv3.1

Homology model for Kv3.1 with gambierol's binding site [1630]

The Kv3.1b channel protein contains two N-glycosylation sites (Asn220 and Asn229) on the extracellular linker between the first (S1) and second transmembrane segments (S2) in mammalian cells [17] and [18]. N-glycosylated Kv channel proteins in heterologous cells exhibit a distinct shift in electrophoretic mobility by SDS–PAGE based on differences in N-linked glycosylation processing of the channel proteins [1631]

Kv3.1 predicted AlphaFold size

Methodology for AlphaFold size prediction and disclaimer are available here

Kv3 activation

Kv3 alpha subunits form channels with ultrarapid activation and deactivation kinetics and an especially depolarized activation voltage, activating only when the membrane potential is more positive than 10 mV. These biophysical properties, combined with the expression patterns of Kv3 alpha subunits in mammalian brain, support a central role for Kv3 channels in determining the ability of neurons to follow high frequency input and sustain rapid firing. [15]

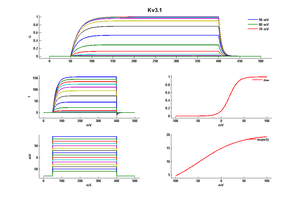

Rat Kv3.1 expressed in CHO cells

Mouse Kv3.1 Expressed in CHO Cells in Mouse Auditory Neurons

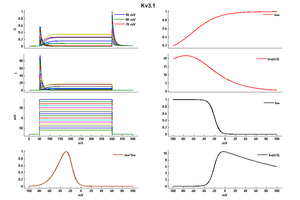

Kv3.1 Kinetics

Deactivation Kinetics

Although Kv3 channel opening starts at high potentials (more positive than -10 mV), the probability of channel opening increases steeply with voltage, and >80% of the channels are opened at +30 mV. The currents deactivate very fast, at rates that are >7–10 times faster (when compared at the same voltage) than those of other known mammalian voltage-gated K+ channels [18]

Single Channel Kinetics

The SNΔ channel is a Shaker B chimera having the S6 segment sequence from mKv3.1. The single-channel recordings of SNΔ channels, similar to those of wild-type Shaker channels, contained many brief closures (flickers). [1636]

Fast voltage-sensor of Kv3.1 reduces refractory period

Kv3 channels are important to reduce the refractory period of neurons due to their high activation threshold and fast closure kinetics enabling high-frequency action potential (hfAP) transmission. Kv3.1b's resurgent currents result from steep voltage-dependent gating kinetics and ultra-fast voltage-sensor relaxation dependent on the S3-S4 loop of the voltage-sensor.[2097]

Markov Model for Kv1.3 Mutant

Hodgkin Huxley Model for Kv3 Channel

It might appear that in activation of the Kv3 current could be modeled using a standard Hodgkin Huxley description and that, because it is so slow, its biological relevance for excitable membranes is question- able. Both of these assumptions are wrong. Inactivation also occurs in response to a series of short pulses of depolarization similar to a sequence of action potentials. Examination of the height of the peaks also reveals that the amount of inactivation increases between the pulses even though the membrane is hyper polarized to a level at which recovery from inactivation would normally occur. This shows that the inactivation does not depend solely on voltage and, thus, that it cannot be described using the standard Hodgkin-Huxley formalism [1837]

Model Kv3.1 (ID=25)

| Animal | Xenopus | |

| CellType | oocyte | |

| Age | 0 Days | |

| Temperature | 23.0°C | |

| Reversal | -65.0 mV | |

| Ion | K + | |

| Ligand ion | ||

| Reference | [279] M Stocker et. al; EMBO J. 1992 Jul | |

| mpower | 1.0 | |

| m Inf | 1/(1+exp(((v -(18.700))/(-9.700)))) | |

| m Tau | 20.000/(1+exp(((v -(-46.560))/(-44.140)))) | |

Model Kv3.1_1 (ID=26)

Error: verification needed for kinetics

| Animal | NA | |

| CellType | NIH fibroblast | |

| Age | 0 Days | |

| Temperature | 22.0°C | |

| Reversal | -80.0 mV | |

| Ion | K + | |

| Ligand ion | ||

| Reference | [282] L K Kaczmarek et. al; J. Neurophysiol. 1995 Jul | |

| mpower | 4.0 | |

| m Alpha | 0.11325*exp(0.025*v) | |

| m Beta | 0.00927*exp(-0.01511*v) | |

| hpower | 1.0 | |

| h Alpha | 0.00173*exp(-0.1942*v) | |

| h Beta | 0.0935*exp(0.0058*v) | |

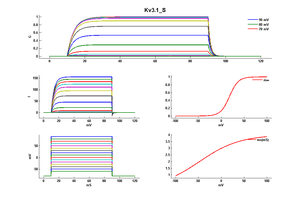

Model Kv3.1_S (ID=27)

| Animal | Xenopus | |

| CellType | oocyte | |

| Age | 0 Days | |

| Temperature | 23.0°C | |

| Reversal | -65.0 mV | |

| Ion | K + | |

| Ligand ion | ||

| Reference | [279] M Stocker et. al; EMBO J. 1992 Jul | |

| mpower | 1.0 | |

| m Inf | 1/(1+exp(((v -(18.700))/(-9.700)))) | |

| m Tau | 4.000/(1+exp(((v -(-46.560))/(-44.140)))) | |

Kv3.1 channels underlie a high-voltage–activating component of the delayed rectifier K+ current in projecting neurons from the globas pallidus. There are two forms, -a and -b, which differ in expression during development. Kv3.1a appears to be found in the neurons of the adult brain, whereas Kv3.1b is expressed in embryonic and perinatal neurons. In addition, Kv3.1 channels can also be found in T-lymphocytes.[18]

Kv3.1b colocalizes with parvalbumin, but not somatostatin, in distinct populations of hippocampal interneurons. Cells that were positive for both parvalbumin and Kv3.lb are depicted by solid squares. Parvalbumin-positive cells that lacked Kv3.lb expression are depicted by stars. [1502]

Kv3.1-Kv3.2 channels underlie a high-voltage–activating component of the delayed rectifier K+ current in projecting neurons from the globas pallidus [18]

The voltage gated K+ channel Kv3.1b is expressed developmentally in the somata, proximal dendrites, and axons of parvalbumin-containing hippocampal interneurons [1502]

Kv3.1b proteins have been found to be expressed in nodes of Ranvier of axons in the medulla and spinal cord, suggesting that Kv3 channels containing these subunits contribute to spike repolarization at the node [318]

Regulation of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b distribution

The distribution of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b to specific cell compartments was shown to be regulated by N-glycosylation.[2095]

Behavioral

Early studies of Kv3.1 single and Kv3.3 single mutants showed physiological changes but revealed, at least initially, only subtle behavioral alterations. In contrast to both single mutants, Kv3.1/Kv3.3 double mutants display a dramatic phenotype: constitutively increased ambulatory and stereotypic motor activity, 40–50% sleep loss, severe ataxia, myoclonus, tremor, and very high alcohol sensitivity.

The findings that Kv3.1 and Kv3.3 channel subunits are expressed at high levels in the cerebellum suggested altered cerebellar function and raised the question as to which behavioral phenotypes originate in the mutant cerebellum and which Kv3-deficient neurons are causally related to these mutant phenotypes. The lack of Kv3.1 channel subunits predisposes to alcohol sensitivity, whereas the absence of Kv3.3 subunits alters olivocerebellar system properties, perturbs normal firing patterns of Purkinje cells, and plays a major role in the observed motor deficits including increased lateral deviation while ambulating, impaired motor performance on a narrow beam, and a predisposition to myoclonus.

To localize the origin of behavioral changes, we targeted re-expression of the missing Kv3.3 channel subunits to Purkinje cells in Kv3.3 single mutants and Kv3.1/Kv3.3 double mutants. Restoration of Kv3.3 activity in Purkinje cells of otherwise Kv3.3-deficient mice sufficed to restore normal lateral deviation and to rescue motor performance on the beam. Restoration of Purkinje cell function was, however, not sufficient to abolish myoclonic muscle twitches and to restore normal alcohol sensitivity. These findings suggest that neurons other than Purkinje cells are responsible for muscle twitches and the effects of alcohol. [300]

Neuronal firing

Together, the experimental data and computer modeling support the idea that the activation range and fast deactivation kinetics of Kv3 channels function specifically to enable neurons to fire repetitively at high frequencies.Kv3 channels might have been a common solution in vertebrates to the problems imposed by high-frequency repetitive firing, as they appear to be present in most neurons that can fire repetitively at high frequencies. It remains to be seen whether there are exceptions to this (such as ‘chattering’ neurons), a finding that would indicate that alternative solutions to achieve high-frequency repetitive firing are used by some neurons.

Kv3 gene products have also been reported in neurons that are not known to fire at high frequencies, suggesting that Kv3 channels might have other physiological roles. Moreover, as described earlier, Kv3 channels are prominently expressed in axons and presynaptic terminals (Fig. 3). The presynaptic function of Kv3 channels remains to be investigated. However, we expect these additional functions of Kv3 channels to be related to their ability to maximize fast action potential repolarization specifically and the consequences of this function: brief action potentials with quick restoration of membrane properties after activity. Consequently, Kv3 channels might be important in regulating the levels of accumulation of intracellular Ca2+, in increasing the fidelity of signal transmission in synapses in which temporal precision is important and in facilitating the faithful transmission of action potentials in particularly active axons by minimizing the accumulation of factors (Na+ channel inactivation, intracellular Ca2+, extracellular ions, etc.) that can compromise the safety factor for action potential transmission [302]

Kv3.1b, the dominant splice variant of Kv3.1, and Kv3.2, channels in rodent cortex, are expressed in PV-positive GABAergic interneurons where they are necessary for facilitating the fast-spiking phenotype in those cells. Indeed, Kv3.1 and Kv3.2 knockout (KO) mice show slower rates of neuronal repolarization than wild type; they show impaired high-frequency firing and demonstrate dysregulated gamma oscillations [1546]

Thalamocortical Oscillation

The genes Kcnc1 and Kcnc3 encode the subunits for the fast-activating/fast-deactivating, voltage-gated potassium channels Kv3.1 and Kv3.3, which are expressed in several brain regions known to be involved in the regulation of the sleep–wake cycle. When these genes are genetically eliminated, Kv3.1/Kv3.3-deficient mice display severe sleep loss as a result of unstable slow-wave sleep. Within the thalamocortical circuitry, Kv3.1 and Kv3.3 subunits are highly expressed in the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN), which is thought to act as a pacemaker at sleep onset and to be involved in slow oscillatory activity (spindle waves) during slow-wave sleep. We showed that in cortical electroencephalographic recordings of freely moving Kv3.1/Kv3.3-deficient mice, spectral power is reduced up to 70% at frequencies <15 Hz [303]

Modulation of cell Proliferation

Immunocytochemical staining revealed K(v)1.3 and K(v)3.1 K(+) channel expression in almost all NPCs. The blockage of K(v)3.1 by low concentrations of TEA, as well as the blockage of K(v)1.3 by Psora-4, increased NPC proliferation. These findings underline the regulatory role of K(+) channels on the cell cycle and imply that K(+) channel modulators might be used therapeutically to activate endogenous NPCs.

Hearing Dysfunction

The data indicate that streptomycin inhibits Kv3.1 currents by inducing a conformational change in the Kv3.1 channel. The hearing loss caused by aminoglycoside antibiotics may be partially mediated by their inhibition of Kv3.1 current in auditory neurons [1831]

Brain stem neurons

Pharmaceutical modulation of Kv3.1 channels induces the adjustment of firing patterns of auditory brain stem neurons. This may hold a therapeutic benefit for the treatment of hearing disorders via the manipulation of neuronal excitability of these cells.[2098]

Kv3.1 and schizophrenia

Kv3.1 channels in interneurons are involved in the pathophysiological mechanism of schizophrenia. Kv3.1 channel openers, like RE1, may therefore have a therapeutic potential in treating deficient interneurons in schizophrenia.[2099]

Kv3.1 heterozygous mutation and MEAK

MEAK - myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia due de novo heterozygous mutation in the KCNC1gene. Kv3 loss disrupts the firing properties of fast-spiking neurons, alters neurotransmitter release and elicits cell death of inhibitory GABAergic interneurons and cerebellar neurons, contributing to myoclonus and seizures and ataxia, respectively.[2100]

Gambierol

Gambierol is a marine polycyclic ether toxin belonging to the group of ciguatera toxins known to inhibit Kv1 K+ channels. While testing whether Kv2, Kv3, and Kv4 channels also serve as targets, we found that Kv3.1 was inhibited with an IC50 of 1.2 ± 0.2 nM, whereas Kv2 and Kv4 channels were insensitive to 1 μM gambierol [1630]

At present there are no specific blockers for Kv3.1 and Kv3.2 channels. However, in Xenopus oocytes all Kv3 currents are blocked by low concentrations of TEA or 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) [18]

Gambierol and Kv3.1 gating

Gambierol was also shown to anchor the gating machinery of Kv3.1 channels in the resting state.[2093]

Kv3.4 Subunits

Kv3.4 subunit coassembles with Kv3.1 subunits in rat brain FS neurons. Coassembly enhances the spike repolarizing efficiency of the channels, thereby reducing spike duration and enabling higher repetitive spike rates. These results suggest that manipulation of K3.4 subunit expression could be a useful means of controlling the dynamic range of FS neurons [1633]

KIF5

Kv3 channels activate KIF5 by relieving the two inhibitory mechanisms that are mediated by the tail-motor and tail-microtubule binding. Kv3 tetramers cluster KIF5 motors via direct and multimeric high-affinity binding, and hence increase the number of KIF5 motors on the carrier vesicle. Therefore, clustering and activation of KIF5 motors by Kv3 regulate the motor number in carrier vesicles containing the channel proteins, contributing not only to the specificity of Kv3 channel transport, but also to the cargo-mediated regulation of motor function [1634]

Fluoxetine

TEA

Kv3.1 is also blocked by low concentrations of TEA [1635]

PSoralen

Psoralen reduced Kv3.1 whole-cell currents in a reversible concentration-dependent manner, with an IC50 value and a Hill coefficient of 2.3 +/- 0.03 microM and 0.9 +/- 0.08, respectively. Psoralen accelerated the decay rate of inactivation of Kv3.1 currents without modifying the kinetics of current activation. The psoralen-induced inhibition of Kv3.1 channels was voltage-dependent, with a steep increase over the voltage range of channel opening. However, the inhibition exhibited voltage independence over the voltage range in which channels are fully activated [1663]

Zinc

Zinc as well as other divalent heavy metal ions regulate the assembly of Kv3 channels, their localization and activity acting on different binding sites. A novel zinc-binding site in the Kv3.1 C-terminus was revealed important for channel activity and axonal targeting[2096]

References

McCrossan ZA

et al.

MinK-related peptide 2 modulates Kv2.1 and Kv3.1 potassium channels in mammalian brain.

J. Neurosci.,

2003

Sep

3

, 23 (8077-91).

Macica CM

et al.

Modulation of the kv3.1b potassium channel isoform adjusts the fidelity of the firing pattern of auditory neurons.

J. Neurosci.,

2003

Feb

15

, 23 (1133-41).

Lewis A

et al.

MinK, MiRP1, and MiRP2 diversify Kv3.1 and Kv3.2 potassium channel gating.

J. Biol. Chem.,

2004

Feb

27

, 279 (7884-92).

Macica CM

et al.

Casein kinase 2 determines the voltage dependence of the Kv3.1 channel in auditory neurons and transfected cells.

J. Neurosci.,

2001

Feb

15

, 21 (1160-8).

Sung MJ

et al.

Open channel block of Kv3.1 currents by fluoxetine.

J. Pharmacol. Sci.,

2008

Jan

, 106 (38-45).

Hernandez-Pineda R

et al.

Kv3.1-Kv3.2 channels underlie a high-voltage-activating component of the delayed rectifier K+ current in projecting neurons from the globus pallidus.

J. Neurophysiol.,

1999

Sep

, 82 (1512-28).

Rettig J

et al.

Characterization of a Shaw-related potassium channel family in rat brain.

EMBO J.,

1992

Jul

, 11 (2473-86).

Kanemasa T

et al.

Electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of a mammalian Shaw channel expressed in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts.

J. Neurophysiol.,

1995

Jul

, 74 (207-17).

Marom S

et al.

State-dependent inactivation of the Kv3 potassium channel.

Biophys. J.,

1994

Aug

, 67 (579-89).

Joho RH

et al.

The role of Kv3-type potassium channels in cerebellar physiology and behavior.

Cerebellum,

2009

Sep

, 8 (323-33).

Henderson Z

et al.

Distribution and role of Kv3.1b in neurons in the medial septum diagonal band complex.

,

2010

Jan

18

, ().

Rudy B

et al.

Kv3 channels: voltage-gated K+ channels designed for high-frequency repetitive firing.

Trends Neurosci.,

2001

Sep

, 24 (517-26).

Espinosa F

et al.

Ablation of Kv3.1 and Kv3.3 potassium channels disrupts thalamocortical oscillations in vitro and in vivo.

J. Neurosci.,

2008

May

21

, 28 (5570-81).

Gan L

et al.

When, where, and how much? Expression of the Kv3.1 potassium channel in high-frequency firing neurons.

J. Neurobiol.,

1998

Oct

, 37 (69-79).

Huang CW

et al.

Experimental and simulation studies on the mechanisms of levetiracetam-mediated inhibition of delayed-rectifier potassium current (KV3.1): contribution to the firing of action potentials.

J. Physiol. Pharmacol.,

2009

Dec

, 60 (37-47).

Joho RH

et al.

Behavioral motor dysfunction in Kv3-type potassium channel-deficient mice.

Genes Brain Behav.,

2006

Aug

, 5 (472-82).

Joho RH

et al.

Kv3 potassium channels control the duration of different arousal states by distinct stochastic and clock-like mechanisms.

Eur. J. Neurosci.,

2006

Mar

, 23 (1567-74).

McDonald AJ

et al.

Differential expression of Kv3.1b and Kv3.2 potassium channel subunits in interneurons of the basolateral amygdala.

Neuroscience,

2006

, 138 (537-47).

Chang SY

et al.

Distribution of Kv3.3 potassium channel subunits in distinct neuronal populations of mouse brain.

J. Comp. Neurol.,

2007

Jun

20

, 502 (953-72).

Du J

et al.

Developmental expression and functional characterization of the potassium-channel subunit Kv3.1b in parvalbumin-containing interneurons of the rat hippocampus.

J. Neurosci.,

1996

Jan

15

, 16 (506-18).

Mishina Y

et al.

Transfer of Kv3.1 voltage sensor features to the isolated Ci-VSP voltage-sensing domain.

Biophys. J.,

2012

Aug

22

, 103 (669-76).

Yanagi M

et al.

Kv3.1-containing K(+) channels are reduced in untreated schizophrenia and normalized with antipsychotic drugs.

Mol. Psychiatry,

2013

Apr

30

, ().

Kopljar I

et al.

A polyether biotoxin binding site on the lipid-exposed face of the pore domain of Kv channels revealed by the marine toxin gambierol.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.,

2009

Jun

16

, 106 (9896-901).

Bae SH

et al.

Src regulates membrane trafficking of the Kv3.1b channel.

FEBS Lett.,

2014

Jan

3

, 588 (86-91).

Gu Y

et al.

Alternative splicing regulates kv3.1 polarized targeting to adjust maximal spiking frequency.

J. Biol. Chem.,

2012

Jan

13

, 287 (1755-69).

Baranauskas G

et al.

Kv3.4 subunits enhance the repolarizing efficiency of Kv3.1 channels in fast-spiking neurons.

Nat. Neurosci.,

2003

Mar

, 6 (258-66).

Barry J

et al.

Activation of conventional kinesin motors in clusters by Shaw voltage-gated K+ channels.

J. Cell. Sci.,

2013

May

1

, 126 (2027-41).

Liebau S

et al.

Selective blockage of Kv1.3 and Kv3.1 channels increases neural progenitor cell proliferation.

J. Neurochem.,

2006

Oct

, 99 (426-37).

Zheng J

et al.

Hidden Markov model analysis of intermediate gating steps associated with the pore gate of shaker potassium channels.

J. Gen. Physiol.,

2001

Nov

, 118 (547-64).

Wang LY

et al.

Contribution of the Kv3.1 potassium channel to high-frequency firing in mouse auditory neurones.

J. Physiol. (Lond.),

1998

May

15

, 509 ( Pt 1) (183-94).

Liu SQ

et al.

Aminoglycosides block the Kv3.1 potassium channel and reduce the ability of inferior colliculus neurons to fire at high frequencies.

J. Neurobiol.,

2005

Mar

, 62 (439-52).

Marom S

et al.

Modeling state-dependent inactivation of membrane currents.

Biophys. J.,

1994

Aug

, 67 (515-20).

Kopljar I

et al.

The ladder-shaped polyether toxin gambierol anchors the gating machinery of Kv3.1 channels in the resting state.

J. Gen. Physiol.,

2013

Mar

, 141 (359-69).

Hall MK

et al.

N-Linked glycan site occupancy impacts the distribution of a potassium channel in the cell body and outgrowths of neuronal-derived cells.

Biochim. Biophys. Acta,

2014

Jan

, 1840 (595-604).

Hall MK

et al.

Complex N-Glycans Influence the Spatial Arrangement of Voltage Gated Potassium Channels in Membranes of Neuronal-Derived Cells.

PLoS ONE,

2015

, 10 (e0137138).

Gu Y

et al.

Kv3 channel assembly, trafficking and activity are regulated by zinc through different binding sites.

J. Physiol. (Lond.),

2013

May

15

, 591 (2491-507).

Labro AJ

et al.

Kv3.1 uses a timely resurgent K(+) current to secure action potential repolarization.

Nat Commun,

2015

, 6 (10173).

Brown MR

et al.

Physiological modulators of Kv3.1 channels adjust firing patterns of auditory brain stem neurons.

J. Neurophysiol.,

2016

Jul

1

, 116 (106-21).

Thelin J

et al.

The translationally relevant mouse model of the 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome reveals deficits in neuronal spike firing matching clinical neurophysiological biomarkers seen in schizophrenia.

Acta Physiol (Oxf),

2016

Jul

1

, ().

Nascimento FA

et al.

Myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia due to potassium channel mutation (MEAK) is caused by heterozygous KCNC1 mutations.

Epileptic Disord,

2016

Sep

14

, ().

Contributors: Rajnish Ranjan, Michael Schartner, Nitin Khanna, Katherine Johnston

To cite this page: [Contributors] Channelpedia https://channelpedia.epfl.ch/wikipages/11/ , accessed on 2025 Dec 08